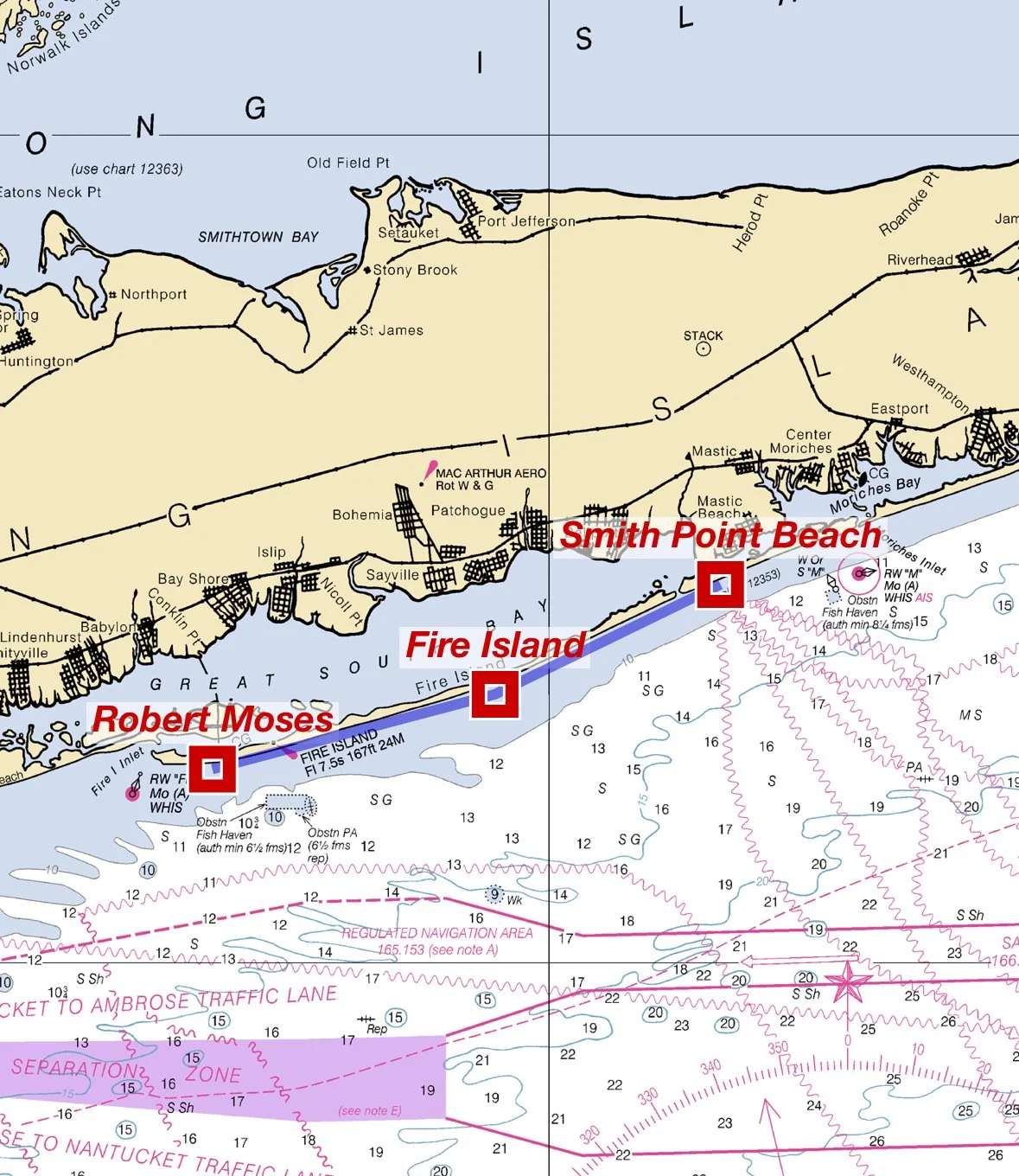

Robert Moses to Smith Point: Prone Paddle

START POINT: Robert Moses State Park Field 3 (Beach Access)

END POINT: Smith Point County Beach

Mode of Travel: Prone Paddle

Distance: 22.7 miles / 19.72 nautical miles

Date of Completion: 10/26/25

Levels of Support: Solo prone paddle, no support (carried all gear).

Trip Report from paddler, Johnny Knapp: “Writing this trip report a day after completing my point-to-point prone paddle on Sunday, October 26th. My body surprisingly feels fine—shoulders and back are all good—but my forearms are humming with pain. Specifically, the inside of my forearms, just above the wrist. The pain started around the time I was passing Davis Park, FI, and it still hasn’t subsided. Very bizarre. Everything else feels great, almost like I didn’t even paddle 22.7 miles the day before. Reaching into my pocket for my phone or keys hurts the worst. It’s been a few years since my first Point to Point challenge back in September 2022—a 16.8-mile (16.6 nautical mile) prone paddle from Westhampton to Bellport. This time, I wanted to up the distance and figured covering nearly all of Fire Island would be a great challenge. Fire Island has always been central to my life; so much of what I do takes place on or around it. The island stretches roughly 32 miles, and I structured my paddle between its two vehicle access points—one at the westernmost end, Robert Moses State Park, and the other at the eastern edge, Smith Point County Beach.

I wasn’t training for this paddle. It was something that had been sitting in the back of my mind for a while, and when the window opened, I just decided to go for it. I usually paddle for exercise when the surf is flat and when the conditions are good in Bellport Bay. It’s a great section of the bay—one I call home, admittedly biased. The stretch from the mainland to the beach is wide enough (about two miles) to get the arms moving, and being protected by Howells Point and Smith Point, it’s generally calmer than other sections of the Great South Bay. I’ll do these big paddles that stretch from a few of the buoys over to the beach and then back to the mainland. Boat traffic is minimal compared to everywhere else, which can feel more like a thoroughfare.

Aside from the occasional deliberate paddle session, my “training” was really just surfing, a regular gym routine, and some road running sprinkled in. I also bike to work in the city. Mentally, though, I was ready. I did a gear check with Drew and asked what he normally takes on his long paddles. He mentioned a 34oz water bottle, electrolyte packets, and some macro bars. I have a few smaller bottles already, but for this I knew I needed something more adequate for the journey. The bars I was good on—I always keep a few of the Laird Superfood Protein + Adaptogen Peanut Butter bars stashed in my surf bag and truck. Walking into Dick’s Sporting Goods was wild. Seeing a “sports store” in 2025 is to be surrounded by a surplus of items—endless options, but not necessarily the best gear. Just enough of the right stuff to get you out there doing whatever it is you’re trying to do. The water bottle section was massive, almost overwhelming. I settled on a generic 32oz bottle that would fit in my rack, close enough to the 34oz I wanted. Spoiler alert: one of the caps broke before the paddle even started—somewhere between purchasing and cleaning it at home. It still made the journey, but this stuff they are selling is pure crap.

Carrying provisions was obviously a concern leading up to the paddle. How would I do it, and what would I bring? I’d experimented over the summer by strapping a dry bag to my prone board during bay crossings, but that setup was too cumbersome.

I thought about using my inflatable swim buoy, which I sometimes tow for open-water swims, but it barely holds anything. Fortunately, I stumbled on a Yeti Sidekick Dry 3L gear bag—a perfect middle ground. I’m not really up on the whole Yeti offering, but I was pretty impressed with this item. In typical fashion, they didn’t carry the strap that was shown on the packaging, so I had to MacGyver it using a strap from the aforementioned inflatable buoy.

To my surprise, it worked perfectly as a bum bag I could wear around my waist, sitting low on my back as I paddled. Inside I stashed two Laird bars, one peanut butter and jelly sandwich, a whistle, and a pair of 3mm Vans booties to throw on if my feet got cold.

My prone board is a 12-foot CoreVac epoxy shaped by AJ Finnan. It gets the job done, but I’ve been longing for something a bit more substantial for longer paddles like these.

The night before the paddle I slept fine—went to bed around 10:30PM and woke at 5:00AM Sunday morning. I immediately made coffee and had a bowl of yogurt, granola, and blueberries with honey to get something in my gut. Before workouts I mix a bottle of Laird Superfood Greens + Thorne Creatine, which I also had that morning. Right before the paddle I ate a banana as well.

Aiming to get there at sunup, which is around 7:15AM this time of year, we pulled into the lot at Field 3, Robert Moses State Park, right on schedule. Surveying the conditions, I was surprised to see more of a sweep coming from the east/southeast than expected. Tide and time wait for no man, and I knew I’d be launching during a less-than-ideal tide—an incoming one, with water pouring into the nearby Fire Island Inlet to the west by Democrat Point. The wind was also up a touch, around 8–10 knots from the north with a hint of northeast. If I wanted to make life easier, I would have reversed the paddle—going from Smith Point west to Robert Moses—but I wanted to end heading east, landing closer to home.

I brought a few wetsuit options that morning since I wasn’t sure what would be best. Too thin and I’d get cold; too thick and I’d overheat. I settled on a straight 3mm with a hood by Feral Wetsuits. This time of year that suit is fantastic—it gets me right up to winter when you need to layer on the heavy rubber. The hood proved a bit cumbersome while paddling, as it pushed my head forward, but overall I was perfectly warm the whole paddle—even my feet. To warm them up, I’d just dunk them in the ocean. I pushed off at 8:05AM and headed east.

There was a laughable amount of boat activity that morning. It’s the fall run for bass, and every fisherman seemed to be out—on shore surfcasting or in boats floating inside and outside the outer sandbar. You could’ve walked boat to boat without getting your feet wet. No judgment, but for me, nature is best enjoyed with the least amount of human activity possible.

It took a while to get into a groove. The current was weird—a refracting chop from the shoreline’s one-foot swell, mixed with a little wind. I aimed quite a distance offshore and maintained about a half-mile from the shoreline during the entire paddle. Out there, I hoped to avoid the refracted energy coming off the beach.

Like I said, if I wanted to make my life easier, I’d have done this paddle in reverse. It felt like forever before I reached the Fire Island Lighthouse, which I passed at 8:50AM. The lighthouse was first commissioned in 1826 and later replaced in 1858—the same one that still stands today.

Passing the lighthouse, I began hitting the Fire Island communities, starting with Kismet. I haven’t spent much time on this end of the island, so I can’t say much about them, except that a few have year-round residents whose kids take a 4x4 bus to school. If you watch some of the Surfline cams in the morning—particularly the Fair Harbor cam—you’ll see a yellow bus bouncing down the beach. What a way to go to school.

For an island off the mainland, this western stretch is surprisingly dense with houses. Look on Google Maps and you’ll see what I mean—homes crammed in next to one another, along with baseball diamonds, tennis and basketball courts, and swimming pools. From the ocean, though, all you see are beach houses lined up side by side, with the large blue water tower at Ocean Beach standing out as the main landmark. I passed it around 10:00AM and took my first water break.

Lone paddler Johnny Knapp passing the Ocean Bay Park cam

For being one continuous sliver of sand, Fire Island is incredibly diverse, and each community has its own quirks. Ocean Beach, for example, is historically known as the “Land of No,” thanks to its long list of restrictions: no bike riding on the boardwalk, no picnicking on the beach, no ball playing—and one historic case in 1977 when two boys were fined for eating freshly baked cookies on the boardwalk. I can’t make this stuff up.

I could tell when I was passing Point O’ Woods—the architecture shifted to classic Victorian cedar shake with white trim and shutters. It’s a private community where not just anyone can buy a house. You have to be reviewed by a board, rent for a year, and only then can you purchase. They’ve got their own post office, grocery store, village association, and yacht club.

Leaving that behind, the next stretch was Sailors Haven, which I reached around 11:00AM. To help time pass, I found it best to fix my focus on the furthest visible point ahead. Eventually that far distance wouldn’t be so far anymore, and I’d shift to the next horizon.

Sailors Haven is part of the Fire Island National Seashore and home to the Sunken Forest—an ecological wonder roughly 300 years old, composed mainly of American holly. The forest sits recessed behind a dune and won’t grow higher than the dune line, creating a flat horizon of treetops when viewed from afar. There are only a few places like it in the world, and Fire Island has one of them.

Next came Cherry Grove, its location marked by the Italian-style palazzo called The Belvedere, visible even from the ocean. Built in 1957 by Broadway set designer John Eberhardt, it’s a Venetian-style resort complete with a Venice flag (a gift from the mayor in the 1960s) and a Pride flag waving beside it.

Between Cherry Grove and The Pines lies a desolate stretch known as The Meatrack. Before dating apps, this was—and still is—a popular cruising zone for men. Within the LGBTQ community, it’s treated as sacred ground and maintained by stewards from neighboring areas.

I reached the middle of The Pines at 11:45AM and took a 15-minute lunch break sitting on my board. I ate my peanut butter and jelly sandwich—the only food I consumed during the journey—and hydrated once or twice an hour. Sitting still, I started to chill a bit, so I was eager to keep moving.

Out there, way offshore, the quiet was peaceful. The only real disturbance was the occasional fisherman zipping around, chasing diving birds that were chasing baitfish that were being chased by larger fish below.

After The Pines came Water Island—a small, tight-knit community of about 50 homes. It’s not private, but residents keep a low profile. If you pull in on the bayside by boat, you won’t get much of a welcome unless you’re with someone they know. There’s a small ferry that runs sporadically to a thin dock. Every August, under the full moon, homeowners throw a legendary beach party—dancefloor on the sand, disco ball above, DJ spinning into the early hours.

Quickly after Water Island is Talisman/Barrett Beach, part of the Fire Island National Seashore and accessible only by private boat. Past that are a few homes around Blue Point Beach, but otherwise, it’s quiet. Heading west to east, the farther you go, the quieter Fire Island gets.

It was around this point that I started feeling it—the forearm pain I mentioned earlier. Just as I was getting to Davis Park. I pulled up to Davis at 1:45PM, near The Casino—a beach bar on the dunes—and took a water break. The Casino is the only true beachfront bar/restaurant on Fire Island; all others are bayside. The island’s signature drink is the Rocket Fuel, and every bar claims to serve the best one. Flynn’s in Ocean Beach really pushes that narrative, but pound for pound, The Casino gets my vote. Many blurry nights and pounding headaches can attest.

Leaving Davis heading east, that’s the last of the infrastructure—no more houses, amenities, or regular ferries. From there, I was truly on my own. Technically, I’d been alone the whole time, way outside the breakers, but at least before that, if something went wrong, I could reach a community. The next landmark, Watch Hill, has no houses but does run a daily ferry.

This stretch—starting around 2:00PM—is probably my favorite. The Otis Pike Fire Island High Dune Wilderness runs from Watch Hill to Smith Point, where I’d finish. It’s the only federally designated wilderness area in New York State. If you want solitude, this is the place. Windswept dunes stretch as far as you can see. The area is home to old shipwrecks that appear and disappear depending on the sand movement. Every few years, the ribs of a wreck will resurface. There are also incredible sandbars—hard to reach, but if you’re willing to hike in, you’ll surf alone.

By 3:00PM I was at Old Inlet—the spot where I planned to text my wife for pickup at Smith Point. I figured by the time she left home, I’d make it there.

The water wasn’t particularly favorable for most of the paddle—lots of wind and chop from Robert Moses to The Pines—but from Bellport Beach past Old Inlet and into Smith Point, the conditions were sublime. The sun came out, the wind laid down, and the current went still. Despite the fatigue, I felt like I was gliding. Whatever spirit was watching over me must’ve given me a gift for the home stretch. One arm, then the next. Over and over. That’s all I had to do.

I set my sights through the water bottle rack on the front of my board, locking onto the Smith Point pavilion and FINS tower. I kept them in view and put my head down. Almost there.

I cruised past the FINS tower, aiming to land right at the base of the stairs leading up to the pavilion. I angled in from the outer bar and paddled toward shore. As I got close, I hopped off to carry my board in—just as a clean one-foot wave broke behind me. I grabbed the tail and dove through it, but the wave knocked my water bottles loose, rolling them in the surf.

A Muslim couple standing at the water’s edge pointed them out to me—the man calling over, the woman in a niqab snapping photos of my landing. That’s the only evidence of the moment that exists.

At 3:50PM, I touched sand.”

- Johnny Knapp

Finish Point Smith Point County Beach